Note from Jane: Today’s guest post is by Sangeeta Mehta (@sangeeta_editor), a former acquiring editor of children’s books at Little, Brown and Simon & Schuster, who runs her own editorial services company. Don’t miss Sangeeta’s earlier contributions, including:

- Self-Publishing Children’s Picture Books: Two Literary Agents Weigh In

- Should Children’s Book Authors Self-Publish?

Even though it’s become quite easy for writers to use Amazon KDP or other platforms to publish an e-book—and use print-on-demand technology to create a professional-looking print book—it’s still rare for literary fiction writers to self-publish.

I asked literary agents Vicky Bijur and Ayesha Pande if and when literary writers should consider this option, how it might affect their long-term careers, and what digital trends we might see in terms of marketing literary fiction.

Sangeeta Mehta: Sales of self-published literary fiction are anemic compared to that of genre fiction, but is this a reflection of the industry as a whole—or because the success of literary writing depends on established, traditional systems that aren’t accessible to self-published writers?

Vicky Bijur: One theory: Genre fiction is read in digital form to a greater degree than literary fiction. That is, readers of genre fiction are used to reading e-books; literary fiction readers a bit less so. Also, there may be many more online blogs/websites, etc., devoted to genre fiction; it may be harder for a reader to find out about literary fiction that is available only digitally. Literary fiction is still review-driven; even though the traditional review media are shrinking, it is still really important to catch the attention of traditional critics, and I think it’s very hard for e-book originals to do that. As recently as 2008 or so a self-published author might still have been selling books to independent bookstores out of the trunk of her car. With the severe reduction in the number of independent bookstores, it much harder to get traction even if your book is in print form.

Ayesha Pande: My response here is based purely on anecdotal evidence: It seems readers of literary fiction have a bias for print books; many readers tell me they want to keep the books, put them on their shelves, read them again and share them with others—none of which is possible with an e-book. In addition, sales of literary fiction still do depend on reviews and self-published books don’t tend to be reviewed by book reviewers, mainly because there are simply too many of them.

Many literary writers embrace the idea of independent publishing, of signing with a small, independent press rather than a media conglomerate. What do you think is preventing these same writers from being as supportive of “indie” publishing? Is it the stigma it continues to face in some circles and writing programs? The onus of having to design and promote their own work in addition to honing their craft? Or the romantic notion that writing is an art, not a business?

AP: A combination of all of the above, but most particularly the understanding that writers are frequently not the best promoters of their own work. There is a skill set required to publish a book and effectively promote it, and most writers I know, who happen to write mostly literary fiction, simply don’t feel qualified to do that. In addition, they would rather spend their time and energy honing their craft rather than learning an entirely new one—publishing and promoting books.

VB: I think there is legitimate concern that if you self-publish you lose all the marketing push that traditional publishers can provide: co-op money for bookstore placement, advertising, early galley mailings to the stores, and so forth. Also, there is something to be said for having the blessing of the gatekeeper and the literary cachet that comes with that.

When considering debut literary writers for their list, most publishers are thinking less about short-term sales and more about the kind of awards and prestige these writers might bring the company down the road. It’s also far easier to market a debut author than one with a track record. By self-publishing, would debut literary writers compromise their most valuable asset: potential? Could self-publishing prevent these writers from landing residencies and being accepted into writing colonies, which are often more favorable to early-career writers?

VB: I can’t help with this question. I don’t know how these residencies look at self-publishing.

AP: I’m not sure I agree that publishers are not thinking about sales; they are running a business after all and ultimately they are anticipating that publishing the book will be profitable for them. Writers who have self-published their book and sold only modest numbers of copies will in all likelihood have a harder time persuading publishers that their books can produce viable sales as compared to debut authors who are starting with a clean slate. I can’t speak with authority about self-publishing being a deterrent to receiving residencies—but I would speculate that to qualify for those it’s the merit of the work that would be the foremost determining factor.

Many agents won’t consider representing a self-published work unless sales are in the high five- or six figures. However, very few works of literary fiction achieve such lofty sales, even with the marketing muscle of a large publisher. Do you have a sales number in mind when considering self-published works? Or would a positive review (from Kirkus or PW, both of which accept self-published books), or an award be more likely to sway you in one direction or the other?

AP: A writer having self-published their work, especially a first novel, wouldn’t necessarily deter me from considering her for representation. I would read the book and assess the merit of the work and make my decision based on that. Many excellent novels do not find publishers and there are many promising authors out there whose work deserves to be published and read. In fact I represent an author who successfully self-published his first two novels.

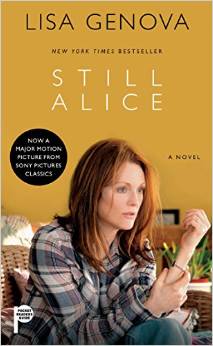

VB: When Lisa Genova approached me with Still Alice in 2008, which she had self-published, I didn’t care about how many copies she had sold. Here’s what I cared about: I couldn’t put down the book; my twenty-three year-old assistant couldn’t put down the book; I thought Lisa’s background as a neuroscientist with a Ph.D. from Harvard University provided her with an instant platform; she had the savvy and the sophistication to have hired a PR firm for her self-published book; she was writing about a topic that had a huge audience; she had already made deep connections within the Alzheimer’s community. That is, the book was spectacular, and it was clear the author was a superstar.

Would you recommend self-publishing to a mid-career client whose option clause has been satisfied by her current publisher—and whose new work isn’t garnering interest from other publishers—as a way of keeping her writing momentum going? Or, rather than publish on their own, is these writers’ time better spent submitting to well-known journals or to new online literary platforms such as Literary Hub or The Offing?

VB: It used to be that writers were discouraged from doing a “small book” in the middle of a career of bigger books, because the chain bookstores—the brick and mortar stores—kept close track of sales, and low sales would hurt the prospects for a writer’s future books. I am not sure that it matters any more if a mid-career book that is published only as an e-book does not do as well as the author’s traditionally published books. I know that often a writer has a book he or she feels must get written before he or she can move on.

AP: I would probably advise such an author against self-publishing in mid-career unless it’s truly the only remaining alternative. A good novel takes a very long time to write and I would ask the author to consider working on building her platform—via residencies, publications in journals, awards and fellowships—or on writing and rewriting—and rewriting—again.

According to The Guardian, literary criticism is still heavily male-dominated, and self-publishing is allowing women to break the book industry’s glass ceiling. If this is the case, shouldn’t more female literary writers take the leap and carve a new space for themselves in the indie landscape?

AP: I don’t think self-publishing is the way for women writers to respond to literary criticism being male dominated. I think we need more diversity in the ranks of literary critics and we need to pressure publications to provide us with a more diverse array of voices.

VB: I am not sure what you mean by “carve a new space in the indie landscape.” What is the point of “carving a new space in the indie landscape” if there is no money to be made there? I would not want to create a ghetto for female literary writers.

Although they aren’t necessarily self-publishing, many writers of literary fiction are experimenting on digital platforms. For example, David Mitchell wrote and delivered his short story “The Right Sort” entirely in tweets, Teju Cole crowdsourced his short story “Hafiz” on Twitter, and the Twitter Fiction Festival is continuing to gain traction. Other writers are publishing digital shorts or flash fiction through their current publishers or online literary sites. What digital trends do you foresee in literary fiction?

VB: I wish I had a crystal ball! I think we cannot begin to imagine how the publishing world will change in the next five years. The word is that e-book sales are plateauing. We may all be reading shorter fiction on our phones or even on our watches. We are waiting to see if Oyster and Scribd will turn into the Netflix of books.

AP: I see writers of literary fiction making increasing use of digital platforms to access and communicate with their readers. Audio seems to be experiencing a revival. Medium, a publishing platform, is attracting many talented authors who are posting their work in the hopes of attracting the attention of readers and publishers. Serialization is something that many publishers are experimenting with.

Vicky Bijur (@VBLA) started her agency in 1988 after working at Oxford University Press and with the Charlotte Sheedy Literary Agency. She represents fiction and non-fiction. In the last few months, three of her books have been on the NY Times bestseller list: Hush Hush by Laura Lippman and Still Alice and Inside the O’Briens by Lisa Genova. Vicky has served as president of the Association of Authors’ Representatives and is currently Chair of its Ethics Committee. She is especially proud of the films that have been made of Drive by James Sallis; Still Alice by Lisa Genova; Every Secret Thing by Laura Lippman; and The Man Who Knew Infinity by Robert Kanigel.

Ayesha Pande (@agent_ayesha) has worked in the publishing industry for over twenty years. Before becoming an agent Ayesha was a senior editor at Farrar Straus & Giroux. She has also held editorial positions at HarperCollins and Crown Publishers. She is a member of AAR (Association of Author’s Representatives), PEN, the Asian American Writer’s Workshop, and sits on the advisory board of the German Book Office. She has attended numerous writing conferences including Muse and the Marketplace, Aspen Summer Words and the Miami Writer’s Institute. She has taught college level courses in editing. She holds a master’s degree from Columbia University. She represents a wide array of fiction, nonfiction and YA.

A former acquiring editor of children’s books at Little, Brown and Simon & Schuster, Sangeeta Mehta (@sangeeta_editor) runs her own editorial services company. Find out more at her website.

Very interesting, particularly for someone whose work is most definitely not genre. And I agree with Vicky, it seems that there are far, far more blogs dedicated to genre–AND to YA/MG–than to literary. How much this impacts ‘discoverability,’ I don’t know.

Given how much people like to stick with the tried and true, the known quantity, I’m always surprised to see how much publishers in particular value debut authors. I’ve always thought people were much more likely to pull the book with the familiar name off the shelf rather than the unknown one.

[…] Should literary writers consider self-publishing? How it might affect their long-term careers? Two agents weigh in. […]

Thanks so much for your comment, Jeff. Yes, traditionally publishers have valued debut authors, so much so that Slate Books and the Whiting Foundation teamed up in the fall to create an award just for second novels, which are often neglected. There’s an excitement about debut authors, and a mystique. You’re right, the YA & MG online communities are large and very supportive. It doesn’t look like self-publishing has taken off in middle grade, though. http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/books/2014/09/we_second_that_prize_for_second_novels_sponsored_by_slate_and_the_whiting.html

That was interesting. Mostly because of the misconception the agents have. One striking one is that self publishing equals ebooks. Yet, it is cheap and easy to publish on paper with POD companies like Ingram Spark.

I wonder what Virginia Woolf’s career would have been like if she did not self publish–OK, she did not self publish, but your husband publishing for you is the next closest thing. And there is the interesting thing. Bloomsbury Press was an artist collaborative that was very influential. Could this be a model for literary publishing today?

After all the reasons not to self publish, the conversation turned to an author that successfully self published.

The other thing that strikes me is the implication that literary fiction authors are from a certain socioeconomic background where they have the means to spend time to “develop their craft.” Most people need to have an income to support their life.

Anyway, it was a revealing discussion.

[…] Link to the rest at Jane Friedman […]

[…] by editrrix / via Flickr Note from Jane: Today’s guest post is by Sangeeta Mehta (@sangeeta_editor), a former acquiring editor of children’s books at Little, Brown and Simon & Schuster, who runs her own editorial services company. Don’t miss… […]

As an indie author who just published literary fiction, I am greatly encouraged by the story of Lisa Genova. Now if just one person in the publishing community who reads “A Portrait of Love and Honor” might have the same reaction . .. they couldn’t put it down! The Genova story gets to the heart of why professional writers such as myself go the indie route . . . it provides not just complete creative control and no worries about a small press and problems inherent with that route, but a way to possibly garner mainstream attention for your work . . .

Very interesting discussion. I went the self-publishing route out of a desire to publish a novel before I die :-), after literally decades of writing novels and shopping them around. I think this is a motivation for many who go this route. But it also led to a deal for my next novel with a small independent press, which was a positive but unanticipated outcome.

This article seems to presume the broadest possible definition of “literary” and that one can only self-publish in digital format. The outlets for truly literary fiction are shrinking, and the small presses that publish it do little more than wave a wand of credibility over the work. They certainly don’t pay and they don’t promote. However, the enterprising author could get in her or his van and, like ye punk rock bands o’ yore, barnstorm the country from city to city, gig to gig, giving readings and selling books over the tailgate. As the bottom continues to fall out of the “culture industry,” this kind of DIY ethos may be all that’s left to us.

What an inspiring story, Audrey. Thanks for sharing. Susan: Hope you find that one agent or acquiring editor who loves your work and is willing to go to bat for it. You might find this article by Porter Anderson helpful, as it’s about how self-publishing is a means to the next stage in your publishing career, not the end (ignore the title of the piece). http://thoughtcatalog.com/porter-anderson/2015/03/is-it-time-for-self-publishers-to-get-over-self-publishing/

Thank you, Sangeetamehta for the link to the Porter Anderson article. I totally agree with him – and have said this for some time now – that there is no point in debating/drawing attention to the merits or lack thereof of self publishing . . . rather “get on with it” in terms of writing another book. At this point in my career, I’m satisfied to have “product” out there . . . garnering attention and readers . . . what happens next . . . who knows?

Susan, Curious about your platform and what you have been up to, I clicked on your name and found nothing. An empty blog page. 🙁