Note from Jane: In 2014, I wrote and published the following article in Scratch magazine. It has been edited and updated for my site.

In a widely shared excerpt from his memoir, My Mistake, publishing industry veteran Daniel Menaker described his first experience trying to acquire a book at Random House. His boss told him, “Well, do a P-and-L for it and we’ll see.”

P-and-L. P&L. Profit and loss. However you refer to it, the P&L is a publisher’s basic decision-making tool for determining whether a book makes financial sense to publish. It’s a mixture of the predictable (such as manufacturing costs) and the unpredictable (namely, sales). Nearly every established book publisher uses a proprietary P&L that it doesn’t disclose.

When I started working at a mid-size book publisher in 1998, P&Ls weren’t required before signing a book unless the book had to survive primarily on bookstore sales. (At the time, this publisher sold many books through its own book clubs and specialty retailers.) By 2001, P&Ls were required for every single title, partly because the publisher went from family ownership to corporate ownership—and because the book business was changing.

As an acquiring editor, it was my responsibility to put together the P&L for every title I proposed and to make sure it would hit the target profit margin before wasting the pub board’s time with a proposal. Pub board was a weekly assemblage of key company players in editorial, sales, and marketing who gave the green light to contract authors and titles. When I started negotiating author contracts, my marching orders were to ensure the author advance didn’t go beyond what the P&L indicated would be earned out through sales of the first print run. (This isn’t the case at every publisher, but I worked for a fiscally conservative house.)

Things have changed dramatically in the 15 years since I saw my first P&L. For starters, more than half of book sales now happen online—but the underlying math remains the same. While no author should ask her publisher to see her book’s P&L, understanding the principles of a P&L can help you better appreciate what financial pressures publishers are under, how a book can quickly become a financial liability if the first print run doesn’t sell through, and why advances might look low to you, but high to a publisher.

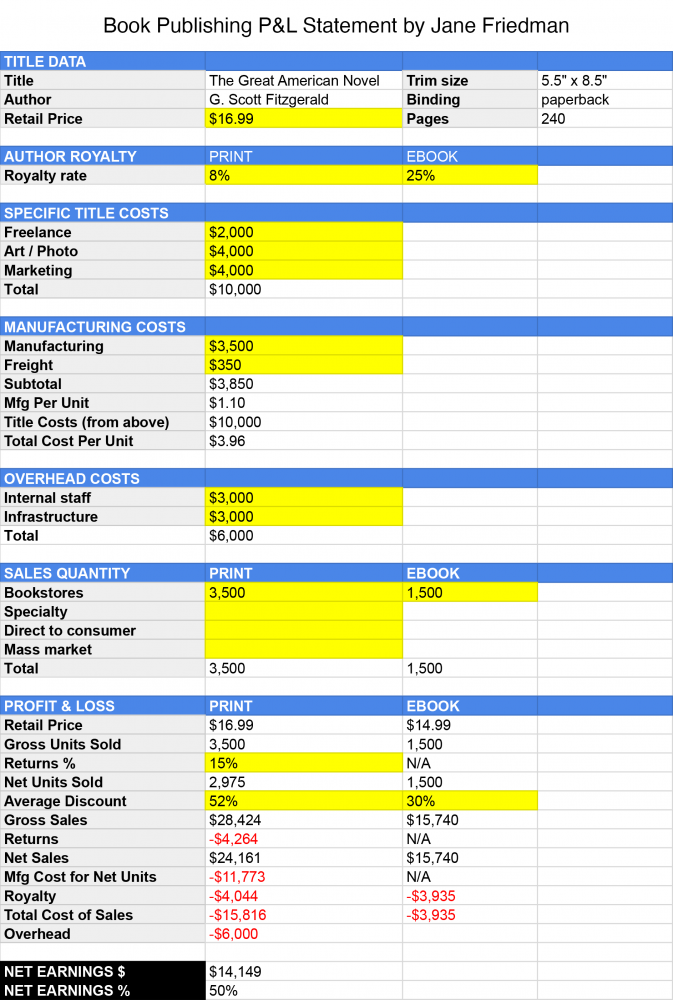

The following P&L is my creation—a from-scratch, stripped-down version of the form a publisher might use. In the breakdown below, I’ll point out areas where I’ve greatly simplified to get the larger point across. Ready to follow along? Visit the Google Doc and use the following text to understand its components.

Title Data

For our example P&L, we’ll use the specs of a typical debut novel issued as a trade paperback original. An average trade paperback is 5.5″ x 8.5″, between 200 and 300 pages (80,000 words), and retails for $14.99 to $19.99.

Why aren’t we going with hardcover? It’s less risky to debut an author in trade paperback; readers are more willing to try an unknown author if the price of the experiment is less than $20.

Author Advance and Sales Quantity

It is nearly impossible to separate the discussion of the advance from sales projections, so we’ll tackle these together. You should be able to make an educated guess at what the publisher thinks it will sell based on your advance (with one caveat, to be explained in a moment).

Daniel Menaker’s discussion of the P&L determined the publisher’s projected sales by working backward from the author’s advance of $50,000. The advance was probably higher than what the author, George Saunders, would ultimately earn out through royalty payments.

Note: Authors receive an advance against royalties; as books sell, authors earn a percentage of sales for each copy sold (a royalty), which is applied against the advance they received. Only once the advance is fully earned out do authors start actually receiving royalty payments. Industry insiders estimate 70 percent of authors do not earn out their advance. Authors do not have to return their advance if the book doesn’t earn out.

For a variety of reasons, it’s fairly common for Big Five houses to offer an advance they know won’t earn out. If you want to look at publishers in an altruistic light, by offering an advance that won’t pay out, they’re essentially agreeing to pay a higher author royalty rate than what’s stated in the contract. (Put another way: they’re fully aware they’re paying an advance that will never be earned back.)

That said, most publishers will calculate an advance after agreeing on a projected sales quantity, which is based on several criteria:

- past sales of the author (or comparable authors, for a debut title)

- the recent performance of the book’s genre/category for the publisher

- subrights deals (such as foreign rights and sales) or the potential for such

- whether the title was auctioned (in an auction, several houses compete for a title, which often leads to the publisher overpaying).

At pub board meetings, the sales and marketing team may commit to specific sales figures by channel. Bookstores, including Amazon, represent the majority of sales for most Big Five titles. Depending on the title or publisher, there may be expectations for direct-to-consumer sales (sales directly to readers through the publisher’s website, for instance), specialty sales (e.g., Home Depot, Anthropologie), and mass-market sales (e.g., Walmart).

Note that P&Ls may be done for a specific time period, such as the first six to twelve months of anticipated sales, or for the lifetime of the book.

Author Royalty

For our example P&L, we have greatly simplified the royalty calculation. Most P&Ls apply a different royalty rate to different types of sales. Authors earn a different rate depending on the format (hardcover, paperback, or ebook) and also depending on the sales channel. P&Ls also take into account escalators, which are the sales thresholds at which an an author earns a higher royalty rate. For example, royalties for a trade paperback might look like this:

- 1–5,000: 8.0%

- 5,001–10,000: 10.0%

- 10,001–20,000: 12.5%

- 20,001 and higher: 15.0%

Hardcover royalties typically start at 10 percent.

Our P&L is for paperback and ebook sales; we’ll pay our author, G. Scott Fitzgerald, an advance that’s roughly equivalent to royalties earned from sales of the first print run.

Specific Title Costs

Any realistic P&L will include the hard costs involved in producing a specific title. In our example, we’ll include basic costs for freelance (copyediting and proofreading), cover design (fees for illustrators or photography, as well as freelance graphic design if needed), and a modest marketing budget. (If we really believed in Mr. Fitzgerald’s book, we’d be looking at a marketing budget well into the five figures.) Other costs that might be included here (not an exhaustive list): ghostwriting, permissions costs if not covered by the author, indexing if not charged against the author, and interior art or illustration costs.

Manufacturing Costs

This is one of the more predictable cost areas. An editor may ask the production department for a manufacturing cost estimate for a title, or the editor may use scale charts that show the unit cost (cost per book) of producing a title based on paper trim size, page count, and print run. As the print run decreases, the unit cost increases. Most publishers have preferred trim sizes to maximize efficiency and savings when printing and shipping. If your book is an unusual trim size, requires interior color printing, or has a high page count, its manufacturing costs will go up.

A good rule of thumb for manufacturing cost: $1 per paperback and $2 per hardcover for offset printing of a black-and-white book at a standard trim, unless you have a very large print run.

Freight costs must also be factored in; estimate about ten cents per unit, assuming domestic printing.

Overhead Costs

Some publishers apply overhead costs to their P&Ls—either specific dollar amounts or a corporately determined percentage that applies to all titles. These costs vary greatly, and may include costs for internal (staff) editorial and design, legal fees, and other infrastructure costs (expensive Manhattan rent, company parties in West Egg, etc.).

Profit & Loss

Here’s where the magic happens! (I won’t say if it’s dark magic or not.) Based on all the data we’ve input into our form, we calculate the financial risk of the debut of The Great American Novel by our next hot author, G. Scott Fitzgerald. A breakdown of the math:

- Retail price. Pulled directly from title data.

- Gross units sold. Pulled directly from sales quantity. These numbers are only as reliable as the person giving the estimate, and are sometimes based on comparable sales of another title in the publisher’s list. (This is why it can be hard for an author with a bad sales record to get another deal.)

- Returns %. Any bookstore can return a book to the publisher for a full refund, whether the sale was made one day ago or ten years ago. Every publisher applies its own average percentage here based on historical return rates by category. The average industry return rate used to be 30 percent. This percentage has declined as ebooks sales have increased, as Amazon sales have grown (Amazon doesn’t return), and as chain bookstores have decreased their orders.

- Net units sold. How many books are sold after returns are factored in.

- Average discount. Our example P&L has tremendously simplified the discount field. Publishers negotiate specific discounts and co-op costs with each account or retailer. Co-op costs are the fees that retailers expect from publishers for in-store marketing and promotion of books. (Not long ago, there was a prolonged kerfuffle between Simon & Schuster and Barnes & Noble about these fees.) We’ve applied a fairly standard 52 percent, since our novel is primarily a bookstore-driven book, and most bookstores receive about a 50 percent discount, in addition to co-op (if any).

- Gross sales. How much money the publisher makes from book sales (with our 52 percent discount), before returns.

- Returns. Subtracts money lost from returns.

- Net sales. How much money the publisher makes from book sales after returns.

- Manufacturing cost for net units. How much it costs to produce the books that are sold, including specific title costs.

- Royalty. What the author earns, assuming he receives 8 percent of every print book sale, based on retail price. Some authors receive a percentage of every sale based on net receipts, or what the publisher receives after discounting. For ebooks, most authors earn 25 percent net. In this example, if we intend for our boy G. Scott to earn out his advance from the first print run, he should receive an advance of about $8,000.

- Total cost of sales. Totals the author royalty and the manufacturing cost on the print side.

- Overhead. Directly pulled from data above.

- Net earnings $ and net earnings %. This is how much profit the book will earn for the publisher (in both print and ebook formats), expressed in both dollars and as a margin percentage.

Does the Great American Novel Pass the P&L Test?

It all depends on the publisher’s measuring stick. Let’s say our editor in chief refuses to contract any book that doesn’t make at least $20,000 or a 45 percent margin. This book might be rejected unless we could find evidence that a higher quantity will be sold, or unless we could somehow cut costs.

A good publisher will typically look at each title as part of a larger season of titles. If your imprint releases 20 titles every season, you should have a mix of higher-earning titles and “quieter” books that are more financially risky. If an editor acquires nothing but books that net the publisher $14,000 each, she might not keep her job for very long. But one or two low-earning books can be subsidized by better-selling titles. That’s why you often hear about the celebrity or blockbuster titles subsidizing the other titles a publisher produces.

At this point, it’s both fun and depressing to play the what-if game:

- What if bookstores take a lower quantity than projected?

- What if the first print run has to be lowered when the book goes to press because the Barnes & Noble buyer doesn’t like the cover?

- What if there are unexpected editorial costs?

- What if this becomes a breakout title and the book goes back to press for another 20,000 copies?

- What if a mass-merchandiser takes 10,000 copies, but at a higher discount of 75 percent?

What About Ebooks?

A few important notes about ebook sales:

- The discount on ebooks is 30 percent if you’re a Big Five publisher.

- The ebook royalty at a Big Five publisher is 25 percent of net receipts, not retail price.

- There are no manufacturing, returns, or freight costs associated with ebooks; some publishers may apply conversion/formatting fees or overhead associated with ebook production.

- Pricing varies, but $12.99–$14.99 is common for a newly released work.

Our example P&L assumes our Great American Novel sells 1,500 copies in ebook form, which is the industry average of 30 percent ebook sales. Note that a significant portion of the total cost of sales in the print column is a shared cost across both formats (the specific title costs plus overhead, which add up to $16,000).

Last year, a slide from a HarperCollins presentation on hardcover-versus-ebook profitability was leaked and made its way around publishing blogs (see below). The slide makes clear what agents and authors have been arguing: the publisher has a higher profit on ebooks, mainly because the author royalty is lower. (You’ll also notice the profitability is being calculated on a hardcover, not a paperback; hardcovers have always been more profitable than paperbacks due to high markup.)

Try It for Yourself

Would you like to run your own P&L? To preserve the formulas working in the background, only modify those cells highlighted in yellow. The spreadsheet will recalculate everything automatically. Don’t forget to change the manufacturing cost when changing sales quantities. Estimate $1 for each paperback unit and $2 for each hardcover unit.

And don’t forget to pick up a copy of The Great American Novel. G. Scott Fitzgerald could really use the royalties.

Jane Friedman has spent nearly 25 years working in the book publishing industry, with a focus on author education and trend reporting. She is the editor of The Hot Sheet, the essential publishing industry newsletter for authors, and was named Publishing Commentator of the Year by Digital Book World in 2023. Her latest book is The Business of Being a Writer (University of Chicago Press), which received a starred review from Library Journal. In addition to serving on grant panels for the National Endowment for the Arts and the Creative Work Fund, she works with organizations such as The Authors Guild to bring transparency to the business of publishing.

Interesting stuff, Jane, thanks for sharing.

One of the things I’m curious about here with your example: the masses rant and rave all the time about the price of e-books and how they shouldn’t be anywhere near the cost of a printed novel. My defense is always the same: editing, proofreading, layout/graphics, overhead, etc. How come none of the specific title costs or overhead are shared across print and e-book version of Fitzgerald’s fantastic work? Or did you simplify for the sake of the example?

My P&L is greatly simplified, so that’s the reason here. However, some publishers’ P&Ls would, in fact, look like this—which I agree isn’t fair. It makes the digital product look more profitable than it actually is.

[…] Publishers use a P&L (profit & loss) statement to determine whether a book makes financial sense to publish. Here's how they work—plus an example form. […]

Wow. This is great. It is so much more informative than indie author P&Ls:

Book + Blog + Facebook + Something = Profit

I do have a question. Your example uses 15% as a return rate. I often here 30% as a return rate. Are there correlates that can influence returns rates–hardcover/paperback, genre, fiction/non-fiction, trade/academic?

Return rates do vary dramatically depending on the publisher, format, category, sales history, promotional campaigns, etc. In the 2000s, the return rate was indeed about 30%. However, that rate has declined due to the increased proportion of online sales and ebook sales (no or minimal returns)–not to mention smaller, more conservative orders from chain stores.

Great article! I’m curious as to how publishers decide on picking up a children’s book and how they evaluate costs and potential earnings. I intend on self-publishing, which is quite a journey. Do you have anything to share in the children’s book world.

Hi Christine – From a P&L perspective, the exact same factors are at play, only you have to factor in costs associated with illustration. The illustrator typically receives a royalty, just like the author. That said, many self-pub authors pay their illustrators a flat fee rather than a royalty.

Here’s a more comprehensive post on self-publishing in the children’s market:

https://janefriedman.com/2015/03/12/self-publish-childrens/

Totally fascinating. Thanks for sharing. How do publishers decide what a “comparable” author is in the case of a debut title?

Ideally, you’re thinking through: “Readers who loved X will also love Y.” You’re trying to audience-match the best you can. For fiction, aside from genre, that often means similarity in theme, style, voice, approach. For nonfiction, you look at what titles are most directly competitive, and authors who have similar platforms.

Hi Jane – This is my first time to your site and I really enjoyed reading this – thanks so much for your easy-to-understand explanation – it’s illuminating! I do have one question though – which I hope doesn’t make me look dense – why isn’t the advance included in the P&L? To me that seems like a definite expense, or, is it a trade-out for the royalties that won’t be paid for this first printing? And is the first printing’s (plus E-book sales) anticipated royalties what is used to determine the advance amount to offer? Thanks!

Hi Cindy – Welcome! For the P&L, the royalty line includes the money the author receives. These royalties get called an “advance” when the author is paid that money before the book is published. This P&L indicates (via the royalty line) that an advance of roughly $8,000 (print + ebook royalty) would be appropriate if we wanted to only pay what we think will be earned out through royalties in the first print run.

Let’s say we offered Fitzgerald $10,000 instead. (Or $5,000!) For this specific P&L, nothing would change. The form helps us determine what amount of advance might actually be earned back, but—at least in the form I’ve created—we don’t add in an extra advance amount if it goes over the calculated earnings. (You could do that, of course!)

Clear and very illuminating. It helps to know that nothing I write would clear the P&L hurdles, so all those doors closed, which is very helpful. I am left wondering how debut authors of fiction ever find a publisher!

Funny enough, debut authors can have an easier time than authors with a poor track record of sales!

Thank you…

Thanks for reading!

[…] How Publishers Make Decisions about What to Publish: The Book PL (Jane […]

I work with a traditional print run small press. How on earth are the big houses getting $1 per print book manufacturing costs? With a print run of 3500 copies, which is what I’m seeing, our cost would still be nearly $3/copy.

Sherry – When you’re publishing hundreds of titles a year and have high volume, that creates efficiencies, as well as having long-standing contracts with specific printers.