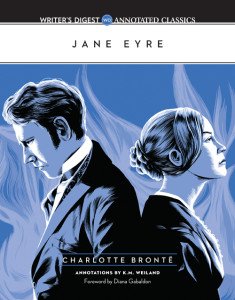

Today’s guest post is by author K.M. Weiland (@KMWeiland), author of the newly released Jane Eyre: Writer’s Digest Annotated Classics.

Conflict in dialogue provides authors with one of their best opportunities for jazzing up their stories and powering their plots. Slow scene? No problemo. Just throw in a nice, heated little argument. What could be easier?

But conflict in dialogue is a little more complex than the Three Stooges would like us to think. If we keep it cranked into the red zone in every scene, readers will grow weary and, eventually, bored.

Conflict can be boring? Who knew?

On its surface, conflict seems to be nothing more than, well, conflict. But if you take a closer look, you’ll be able to identify four distinct types of conflict—all of which are necessary to create a strong and rounded story. To reach full effectiveness, conflict must be varied. Some of your scenes will require full-on red-zone confrontations, but others—depending on the featured characters and what is at stake for them—will be better served by the faintest undercurrent of tension.

In analyzing Charlotte Brontë’s brilliant classic Jane Eyre (which I discuss in-depth in my book Jane Eyre: The Writer’s Digest Annotated Classics), I discovered four different—and equally vital—types of conflict you can use to pop your story’s dialogue right off the page.

Jane vs. Helen Burns: Opposing Views, No Stakes

Early on in Jane Eyre, when Jane is still a student at the grim Lowood School for Girls, she and her best friend Helen Burns engage in a dialogue exchange that features the lowest level of conflict—that of opposing views.

In this discussion, Jane and Helen are arguing opposite perspectives about how to handle persecution. Impassioned Jane is all about defying unjust authority, while patient Helen suggests a more long-suffering and practical approach. Both characters are adamant in their beliefs, but they’re not so much arguing as they are presenting opposing viewpoints.

In this kind of conflict, the characters have little or nothing at stake. Neither of them entered the discussion with important goals. They’re not even all that invested in trying to get the other person to change her mind. The low-key conflict offers no threat to the stability of this important relationship, but still manages to give the scene the pep it would otherwise lack if both girls were simply discussing an agreed-upon belief.

Jane vs. Edward Rochester: Opposing Views, With Stakes

Conflict is created when your character wants something that is then blocked by an external obstacle—often one initiated by another character with an opposing goal. Sometimes that goal will be intangible even and unconscious on your protagonist’s part. On the outside, she will want something concrete in every scene. But the best scenes will often have a secret inner life, in which the context of the dialogue reveals something deeper at stake.

Jane’s conversations with her mysterious employer Edward Rochester are at the heart of this love story’s conflict. But in many of the scenes, Jane and Rochester aren’t at direct odds with one another. They behave as friends should: with good intentions and a desire to understand one another’s viewpoints.

But that doesn’t mean more isn’t going on under the surface.

Like Jane and Helen, Jane and Rochester often discuss moral viewpoints. Jane usually stands on the high ground of unflinching integrity, while Rochester argues for compassion and forgiveness against mankind’s erring nature. On the surface, these lively discussions seem akin to the more low-key conversations Jane had with Helen. But the crucial difference—and the reason these conversations are cranked up a notch on the conflict meter—is that both characters have something at stake.

Even when they don’t come out and state it, they’re each arguing their worthiness to be loved by one another. Rochester is arguing he should be forgiven for his past mistakes—even the current one hidden away in his attic. And Jane is arguing she deserves to be loved without having to enslave her body and spirit.

The characters aren’t arguing, in the sense that their scenes contain any kind of animosity. But the level of conflict has risen right along with the stakes.

Jane vs. the Gypsy Woman: Opposing Goals, Low Stakes

Finally, we reach our first instance of outright conflict, thanks to the fact that both characters have obvious and opposing scene goals. This next stage of conflict isn’t about the subtext (although that can still certainly play a role). This stage is about what both characters are willing to proclaim they want—and then fight for, if only in a civilized way.

Just before the midpoint of the novel, Jane encounters a strangely prescient gypsy woman (who turns out to be Rochester in disguise). The gypsy’s goal is to get Jane to admit she loves Rochester. Jane’s goal is to find out what the gypsy is really up to without giving away any information of her own.

Thanks to their opposing goals, these two characters are in conflict with each other right from the beginning of the scene. Their dialogue exchange bears little personal animosity, but neither does it bear trust. The stakes aren’t critical, but they’re blatant enough to be obviously important to both characters—and, by extension, to the readers.

Jane vs. St. John Rivers: Opposing Goals, High Stakes

When you’re ready to crank your dialogue’s conflict into the red zone, you need to check three elements off your list:

- Give the characters opposing goals.

- Raise the stakes.

- Raise the antagonism.

In this kind of scene, your characters each want something the other is determined not to give him. Even more importantly, they want it badly. If they can’t get what they need, disasters will ensue. As a result of those raised stakes, emotions will be running high. The very fact that another character is standing in the way of the protagonist’s achieving this vital goal will likely cause the protagonist to experience some pretty heated emotions. This is where tempers flare, wild threats are made, and screaming matches ensue. Any more conflict, and your characters will abandon dialogue altogether and dive into physical violence.

Toward the end of the book, Jane engages in a passionate and desperate exchange with her final antagonist: her upright, but cold and calculating cousin, St. John Rivers, who wants her to abandon Rochester forever and become a missionary in India. As the climax approaches, Jane and St. John throw at each other everything they’ve got. They’re both invested up to their necks in their opposing goals. If Jane were to give in now, she would lose everything, including her self-respect.

High-stakes dialogue exchanges such as this one provide just as much, if not more, tension and excitement than any amount of gunplay. But, as you can see, these high-conflict scenes must be balanced throughout your story with the various levels of lower-conflict dialogue. If your highest level of conflict is going to be able to bring its full intensity to bear on readers, it has to be saved for only the most important scenes.

Pay attention to the rhythms of each dialogue exchange in your story and the importance of your characters’ goals. Craft the intensity to match the needs of each scene, and your story’s conflict will rivet readers to every page.

If you enjoyed this post, then don’t miss Jane Eyre: The Writer’s Digest Annotated Classics by K.M. Weiland.

K.M. Weiland lives in make-believe worlds, talks to imaginary friends, and survives primarily on chocolate truffles and espresso. She is the IPPY and NIEA Award-winning and internationally published author of the Amazon bestsellers Outlining Your Novel and Structuring Your Novel. She writes historical and speculative fiction from her home in western Nebraska and mentors authors on her award-winning website Helping Writers Become Authors.

Thanks so much for having me today, Jane!

I have loved this novel for years. Thank you for a deeper insight into it.

It’s an incredible book. Not perfect, but the parts that are perfect are insanely good. I learned so much in annotating it.

Wow, K.M. I LOVE how you’ve taken a classic and gave it even more relevance to writers today by teaching us different types of conflict. Thanks!

It was a crazy-good learning experience for me too. I totally recommend authors analyzing classics for themselves.

Thanks for responding, K.M. I do that with a lot of books. I always read FIRST as a reader and enjoy the story. Then, if I really love it, I got back and read it again as an student, analyzing everything.

Smart!

Very interesting and well written. I loved the examples. Thanks KM!

Glad you enjoyed it!

[…] The 4 Different Types of Conflict in Dialogue […]

[…] If readers can’t connect with our characters, then the story fails. Mary Kole discusses character buy-in as a means to reader buy-in for your world, and Josh Weil suggests planting the seeds of your characters’ emotions early. C.S. Lakin reminds us that secondary characters must have their own needs, and K.M. Weiland lays out the 4 kinds of conflict in dialogue. […]

[…] gifted to instruct and guide writers. Here she shares 4 different types of conflict in dialogue. https://janefriedman.com/2014/07/30/conflict-in-dialogue/ 4) I’ve only recently learned about the existence of Beta readers. Amanda Shofner shares an […]

[…] you look at your dialogue. You have the basics… basics… and MORE basics down […]