Note from Jane: This is a cornerstone post of my site, regularly updated.

Whenever you decide to directly quote, excerpt, or reproduce someone else’s work in your own—whether that’s a book, blog, magazine article, or something else—you have to consider, for each use, whether or not it’s necessary to seek explicit, legal permission from the work’s creator or owner.

Unfortunately, quoting or excerpting someone else’s work falls into one of the grayest areas of copyright law. There is no legal rule stipulating what quantity is OK to use without seeking permission from the owner or creator of the material. Major legal battles have been fought over this question, but there is still no black-and-white rule.

However, probably the biggest “rule” that you’ll find—if you’re searching online or asking around—is: “Ask explicit permission for everything beyond X.”

What constitutes “X” depends on whom you ask. Some people say 300 words. Some say one line. Some say 10% of the word count.

But any rules you find are based on a general institutional guideline or a person’s experience, as well as their overall comfort level with the risk involved in directly quoting and excerpting work. That’s why opinions and guidelines vary so much. Furthermore, each and every instance of quoting/excerpting the same work may have a different answer as to whether you need permission.

So there is no one rule you can apply, only principles. So I hope to provide some clarity on those principles in this post.

When do you NOT need to seek permission?

You do not need to seek permission for work that’s in the public domain. This isn’t always a simple matter to determine, but as of Jan. 1, 2020, it includes any work published before 1926. (As of Jan. 1, 2022, it will include any work published before 1927. And so on.)

Some works published after 1926 are also in the public domain. Read this guide from Stanford about how to determine if a work is in the public domain.

You also do not need to seek permission when you’re simply mentioning the title or author of a work. It’s like citing a fact. Any time you state unadorned facts—like a list of the 50 states in the United States—you are not infringing on anyone’s copyright.

It’s also fine to link to something online from your website, blog, or publication. Linking does not require permission.

Finally, if your use falls within “fair use,” you do not need permission. This is where we enter the trickiest area of all when it comes to permissions.

What constitutes “fair use” and thus doesn’t require permission?

There are four criteria for determining fair use, which sounds tidy, but it’s not. These criteria are vague and open to interpretation. Ultimately, when disagreement arises over what constitutes fair use, it’s up to the courts to make a decision.

The four criteria are:

- The purpose and character of the use. For example, a distinction is often made between commercial and not-for-profit/educational use. If the purpose of your work is commercial (to make money), that doesn’t mean you’re suddenly in violation of fair use. But it makes your case less sympathetic if you’re borrowing a lot of someone else’s work to prop up your own commercial venture.

- The nature of the copyrighted work. Facts cannot be copyrighted. More creative or imaginative works generally get the strongest protection.

- The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the entire quoted work. The law does not offer any percentage or word count here that we can go by. That’s because if the portion quoted is considered the most valuable part of the work, you may be violating fair use. That said, most publishers’ guidelines for authors offer a rule of thumb; at the publisher I worked at, that guideline was 200-300 words from a book-length work.

- The effect of the use on the potential market for or value of the quoted work. If your use of the original work affects the likelihood that people will buy the original work, you can be in violation of fair use. That is: If you quote the material extensively, or in a way that the original source would no longer be required, then you’re possibly affecting the market for the quoted work. (Don’t confuse this criteria with the purpose of reviews or criticism. If a negative review would dissuade people from buying the source, this is not related to the fair use discussion in this post.)

To further explore what these four criteria mean in practice, be sure to read this excellent article by attorney Howard Zaharoff that originally appeared in Writer’s Digest magazine: “A Writers’ Guide to Fair Use.”

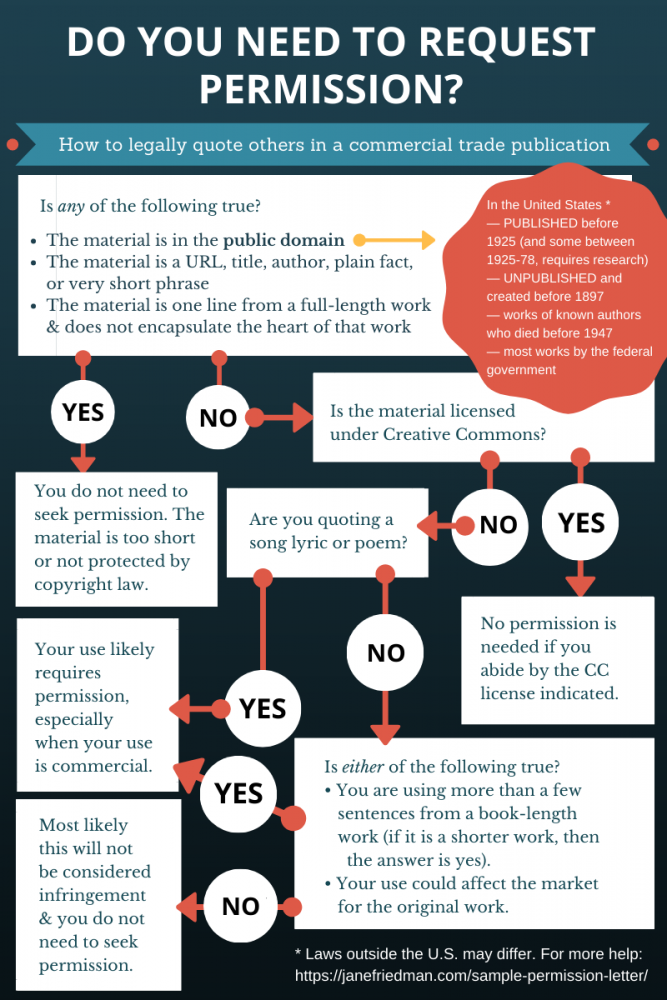

In practice, if you’re only quoting a few lines from a full-length book, you are most likely within fair use guidelines, and do not need to seek permission. But to emphasize: every case is different. Also, much depends on your risk tolerance. To eliminate all possible risk, then it’s best to either ask for permission or eliminate use of the copyrighted material in your own work. Here’s a flowchart that can help you evaluate what you might need to ask permission for.

Three important caveats about this chart

- Nothing can stop someone from suing you if you use their copyrighted work in your published work.

- The only way your use of copyright is tested is by way of a lawsuit. That is, there is no general policing of copyright. Therefore, how you handle copyrighted content depends on how risk averse you are. If you decide not to seek permission because you plan to use a fair use argument, be prepared with the best-possible case to defend your use of the copyrighted content in the event that you are sued.

- If you intend to produce material that is accessible worldwide and in digital form (such as content on the internet, ebooks, etc), and if you are using content considered in the public domain in the United States, you should double-check whether the content is also in the public domain in other countries. You can learn more about this issue in The Public Domain by Stephen Fishman.

If you’re concerned about your risk, you can also search for the rights owner’s name and the keyword “lawsuit” or “copyright” to see if they’ve tried to sue anyone. However, just because someone hasn’t sued yet doesn’t mean they won’t sue you.

If you seek permission, you need to identify the rights holder

Once you’ve decided to seek permission, the next task, and one of the most difficult, is identifying who currently holds the copyright or licensing to the work. It will not always be clear who the copyright holder is, or if the work is even under copyright. Here are your starting points.

- First, verify the actual source of the text. Sometimes writers use quotes from Goodreads or other online sources without verifying the accuracy of those quotes. (As someone who is misattributed on Goodreads, I can confirm: people are misattributed all the time.) If you don’t know the source, and you don’t know the length of the source work, and you don’t know if what you are quoting is the “heart” of the work, then you are putting yourself at risk of infringement.

- If you’re seeking permission to quote from a book, look on the copyright page for the rights holder; it’s usually the author. However, assuming the book is currently in print and on sale, normally you contact the publisher for permission. You can also try contacting the author or the author’s literary agent or estate. (Generally, it’s best to go to whomever seems the most accessible and responsive.)

- If the book is out of print (sometimes you can tell because editions are only available for sale from third parties on Amazon), or if the publisher is out of business or otherwise unreachable, you should try to contact the author, assuming they are listed as the rights holder on the copyright page.

- You can also check government records. Most published books, as well as other materials, have been officially registered with the US Copyright Office. Here is an excellent guide from Stanford on how to search the government records.

- For photo or image permissions: Where does the photo appear? If it’s in a newspaper, magazine, or an online publication, you should seek permission from the publication if the photo is taken by one of their staff photographers or otherwise created by staff. If you’ve found the photo online, you need to figure out where it originated from and/or who it’s originally credited to. (Try using Google Image Search.) When in doubt, seek permission from the photographer, keeping in mind that many photographers work through large-scale agencies such as Getty for licensing and permissions. Photo permissions can get complex quickly if they feature models (you may need a model release in addition to permission) or trademarked products. Here is an excellent, in-depth guide if you need it: Can I Use That Image?

Generally, you or your publisher will want nonexclusive world rights to the quoted material. “Nonexclusive” means you’re not preventing the copyright owner from doing whatever they want with the original material; “world rights” means you have the ability to distribute and sell your own work, with the quoted material, anywhere in the world, which is almost always a necessity given the digital world we live in.

Also, permission is generally granted for a specific print run or period of time. For example, if you seek permission for a 5,000-copy print run, you’ll need to secure permission a second time if you go back to press. (And if you publish a second edition, you’ll need to seek permission again.)

A possible solution for some authors: PLSclear

PLSclear, a UK firm, can help secure permissions. It is a free service; here is the list of publishers that participate.

If you’re under contract with a publisher

Just about every traditional publisher provides their authors with a permissions form to use for their project (be sure to ask if you haven’t received one!), but if you’re a self-publishing author, or you’re working with a new or inexperienced house, you may need to create your own.

To help you get started, I’ve created a sample permissions letter you can customize; it will be especially helpful if you’re contacting authors or individuals for permission. It will be less necessary if you’re contacting publishers, who often have their own form that you need to sign or complete.

To request permission from a publisher, visit their website and look for the Permissions or Rights department. Here are links to the New York publishers’ rights departments, with instructions on how to request permission.

- Harpercollins permissions information

- Penguin Random House permissions portal

- Macmillan permissions

- Simon & Schuster permissions

- Hachette permissions

Will you be charged for permission?

It’s hard to say, but when I worked at a mid-size publisher, we advised authors to be prepared to pay $1,000–$3,000 for all necessary permissions fees if they were quoting regularly and at length. (Publishers don’t cover permissions fees for authors, except in special cases.) If you’re seeking permission for use that is nonprofit or educational in nature, the fees may be lower or waived.

What if you don’t get a response or the conditions are unreasonable?

That’s unfortunate, but there is little you can do. If you can’t wait to hear back, or if you can’t afford the fees, you should not use the work in your own. However, there is something known as a “good faith search” option. If you’ve gone above and beyond in your efforts to seek permission, but cannot determine the copyright holder, reach the copyright holder, or get a response from a copyright holder (and you have documented it), this will be weighed as part of the penalty for infringement. This is not protection, however, from being sued or being found guilty of infringement.

How to avoid the necessity of seeking permission

The best way to avoid seeking permission is to not quote or excerpt another person’s copyrighted work. Some believe that paraphrasing or summarizing the original—rather than quoting it—can get you off the hook, and in some cases, this may be acceptable. Ideas are not protected by copyright, but the expression of those ideas is protected. So, putting something in your own words or paraphrasing is usually okay, as long as it’s not too close to the way the original idea was expressed.

You can also try to restrict yourself to using work that is licensed and available under Creative Commons—which does not require you to seek permission if your use abides by certain guidelines. Learn more about Creative Commons.

What about seeking permission to use work from websites, blogs, or in other digital mediums?

The same rules apply to work published online as in more formal contexts, such as print books or magazines, but attitudes tend to be more lax on the Internet. When bloggers (or others) aggregate, repurpose, or otherwise excerpt copyrighted work, they typically view such use as “sharing” or “publicity” for the original author rather than as a copyright violation, especially if it’s for noncommercial or educational purposes. I’m not talking about wholesale piracy here, but about extensive excerpting or aggregating that would not be considered OK otherwise. In short, it’s a controversial issue.

Does fair use and permissions apply to images, art, or other types of media?

The same rules apply to all types of work, whether written or visual.

Typically, you have to pay licensing or royalty fees for any photos or artwork you want to use in your own work. If you can’t find or contact the rights holder for an image, and it’s not in the public domain, then you cannot use it in your own work. You need explicit permission.

However, more and more images are being issued by rights holders under Creative Commons rather than traditional copyright. To search for such images, you can look under the “Creative Commons” category at Flickr or VisualHunt.

Note: If you find “rights-free images,” that doesn’t mean they are free to use. It simply means they are usually cheaper to pay for and overall less of a hassle.

No permission is needed to mention song titles, movie titles, names, etc.

You do not need permission to include song titles, movie titles, TV show titles—any kind of title—in your work. You can also include the names of places, things, events, and people in your work without asking permission. These are facts.

But: be very careful when quoting song lyrics and poetry

Because songs and poems are so short, it’s dangerous to use even 1 line without asking for permission, even if you think the use could be considered fair. However, it’s still fine to use song titles, poem titles, artist names, band names, movie titles, etc.

If you want to consult with someone on permissions

I recommend my colleagues at Copy Write Consultants, who have experience in permissions and proper use of citations.

For more help

- 12 Copyright Half-Truths by Lloyd Jassin at CopyLaw—addresses mistaken beliefs commonly held by authors; Jassin’s entire blog is very useful and worth reading

- Citizen Media Law: Works Not Covered By Copyright

- Is It Fair Use? 7 Questions to Ask Before You Use Copyrighted Material by lawyer Brad Frazer

- Copyright Office FAQ: very helpful—addresses recipes, titles, ideas, names, and more

- Very helpful interview with Paul Rapp, an intellectual property rights expert, over at Huffington Post. Discusses song lyrics, mentioning famous people, what constitutes fair use, and much more.

- Are You Worried Your Work or Ideas Will Be Stolen?

Sample Permissions Letter

Jane Friedman has spent nearly 25 years working in the book publishing industry, with a focus on author education and trend reporting. She is the editor of The Hot Sheet, the essential publishing industry newsletter for authors, and was named Publishing Commentator of the Year by Digital Book World in 2023. Her latest book is The Business of Being a Writer (University of Chicago Press), which received a starred review from Library Journal. In addition to serving on grant panels for the National Endowment for the Arts and the Creative Work Fund, she works with organizations such as The Authors Guild to bring transparency to the business of publishing.

[…] https://janefriedman.com/2014/12/17/sample-permission-letter/ […]

Thank you for explaining this to us. I have been searching, and this is the clearest explanation I have found. I am certainly going to use your sample letter. I’m seeking permission to use a paragraph from a couple of old (1917-1926) newspapers (with credit, of course), and I think I can adapt your letter to my needs. (My middle grade novel is set during World War I.) I hope I get a positive response!

Thank you so much! This is just what I’ve been looking for to get permissions for a memoir that I am self-publushing.

Excellent—good timing then. 🙂

[…] If you need to request permissions from an author or publisher, here are general guidelines, plus a sample letter you can customize. […]

You’ve given us a really fabulous resource, Jane! Thanks for clarifying so much about the permissions process.

Happy to help!

[…] Requesting Permissions + Sample Permissions Letter […]

Jane, this is fantastic information. Thank you!!

[…] When you publish there are many details you need to track, especially if you self-publish. Roz Morris answers the question: should you use the free CreateSpace ISBN or your own ISBN? Sometimes you need to get permission to use lyrics, prose, or poetry from other artists in your work. Jane Friedman explains how to request permission and gives a sample letter. […]

Hi Jane, I have been reading some of your past blogs on this subject–including the comments and replies (your patience seems to know no bounds.)

I have a writing blog, and with each post I take a still from a famous movie (ranging from “The Bells” to “Star Wars” to “Pulp fiction”) and add a “funny” tag line. The picture is not relevant to the blog but the tag line I create is.

The first question I have to I need permission for the blog?

Secondly, I eventual hope to take one group of blogs (Quick 5 point guide to XXX) and make an e-book to give away FREE for subscribers. Do I need permission to use the movie stills here?

Thanks Kevin

Fair use & permission (as described in this post) apply to movie stills the same as text, and so it’s a significant gray area. Some of that is addressed here: http://www.reelclassics.com/Buy/licensing.htm

I’d be cautious. While I know this kind of activity is prevalent online (especially with memes), it doesn’t mean people are on the right side of copyright law.

Thank you Jane.

Hi Jane thank you for your article. I am currently writing a book so this helps a lot. I have a question however.

The source that I am requesting to use quotes from is non-fiction. If i do not get permissions, Is it possible to summarize the information in my own words instead of using direct quotations and then use a citation. This is sort of a loop hole instead of directly quoting the source.

It is based on the implication that direct quotes are more valuable than citing facts.

James

Hi James, You don’t need permission to paraphrase—but of course you should cite the source.

Thank you,

I think you are right but just to be more clear, In my particular case, there is a martial arts sect called Tzu Dawn. Basically 2 students have studied directly with the master and both students wrote their own separate books with their experiences studying the school.

I am a fanatic of the art. So my book compiles the information gathered from both of the student’s books in order to further explain my own concepts and ideas within the system, im taking people to the next level. Both of the students books are non-fiction.

i think the problem is that a large sum of the information in my book only comes from 2 sources, which are the only two available.

Then I’d ask for permission to be safe.

Hi Jane, do you know if I am allowed to quote people from public interviews in my book?

A person was speaking on a YouTube video free to the public, can i quote them in my book?

I’m afraid there are too many variables in both situations for me to offer a definitive answer. When in doubt, ask permission.